Some Observations from Switzerland

What a week of trains, walks, and free time revealed about systems, trust, and infrastructure

Switzerland was never on my radar. I first visited almost randomly last year when I was in Milan and looking for a one-day city trip & I discovered Lugano.

Since then, I was impressed. The quality of a country doesn’t show in its top 1% neighborhoods. You can manufacture those anywhere. What matters is the average city, the tier-3 town. That’s where systems and public policy reveal themselves.

To close 2025, I took a week off in Switzerland, bought the Swiss Pass for unlimited trains, and crossed the country. Just trains, cities, walks, and free time to observe.

The first thing you notice is that everything works. Here’s what stood out for me. Some of this might be obvious, and some comparisons might seem unfair or useless given the gap in GDP per capita, and the difference in the history of each country. Still, it was surprising for someone coming from Meknes in Morocco :)

1. Transportation as a Productivity and Simplicity Engine

I paid around €400 for a seven-day Swiss Travel Pass. I got unlimited trains and city transport. At first, it sounds expensive. By the end, it felt like a bargain, not only due to money saved, but also due to the friction removed. I could wake up and decide to go to any city without planning or booking. You just get on the train.

What really struck me is capillarity and the frequency. The network doesn’t just connect big hubs. It reaches everywhere: small towns, medium cities, peripheral places. SBB operates around 8,000 trains per day on long-distance and regional routes. There’s a video from Johnny Harris, an American journalist and YouTuber, who stress-tested the system by visiting all 26 cantons in less than 24 hours using only public transport and succeeded.

Switzerland didn’t build trains to be fast. It built them for synchronization. The idea is simple but radical: trains arrive in major cities just before the hour or half-hour, and depart just after, every time, all day. That single principle drives everything else. If a route from City A to City B takes 58 minutes, that’s infinitely better than 62 minutes. Why? Because trains arrive at :55, passengers transfer, and trains depart at :00. If they miss this window, the whole network breaks.

So Switzerland invested billions to fit routes into 30, 60, or 120-minute intervals. They design the timetable first, then ask what infrastructure is missing to make it work, then build exactly that. This logic explains why so many tunnels exist.

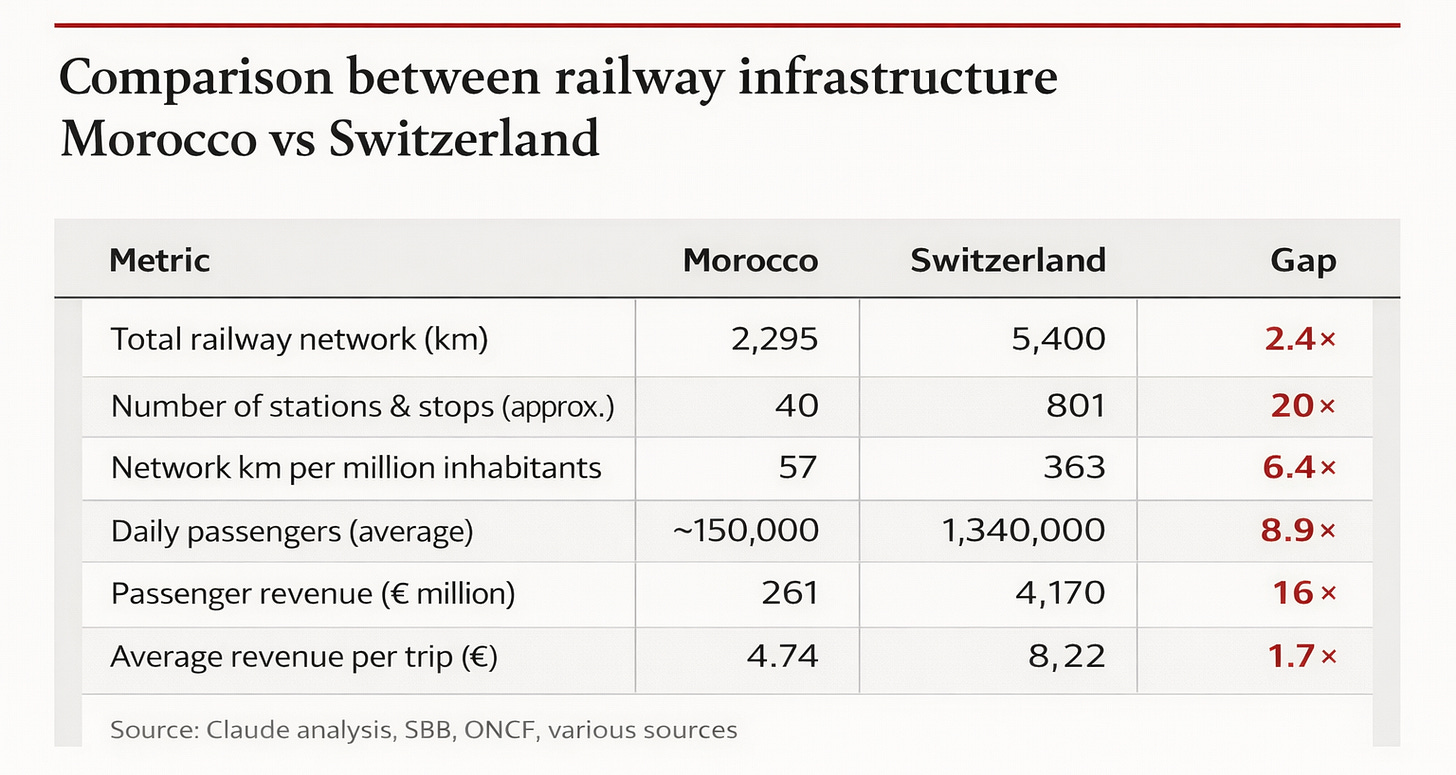

Out of curiosity, I compared Switzerland’s rail network to Morocco’s. Morocco is clearly betting first on speed via TGV. I know people who had businesses in Casablanca and expanded to Tangier simply because the train made it a two-hour trip. What matters most for GDP growth? Capillarity or speed? I don’t know. Transportation infrastructure is one of those things that are very expensive, whose impact is hard to quantify but impossible to overstate.

2. Trust as Infrastructure

One pattern kept appearing everywhere: trust. When a system assumes good faith by default, the cost of doing business collapses. On trains, there are no gates, no hard controls. That single choice removes layers of cost: infrastructure, staff, time and more importantly, hostility between the system and the user. It’s also true that the “trust infrastructure” partly exists because Switzerland is very selective about who gets in.

I tried to get into the National Library of Zurich and the University of Zurich to see if there would be any barrier. I ended up having coffee for free and reading the latest edition of The Economist and The New Yorker, without any obstacle.

Another implication of high trust is the self-service penetration in retail. You find it everywhere, and the quality is good. I was surprised to see so many Zebra scanners in Coop supermarkets. You can get a handheld scanner at the store entrance. You scan items as you shop, drop them in your bag, and pay at a machine on your way out.

What would be the GDP impact due to lack of trust in low-trust environments?

This question triggered me, so I looked for economics papers about it. There’s a lot of research confirming that when trust is low, societies spend more GDP on “verification” (controls, paperwork, intermediaries, enforcement) and invest less because every transaction feels riskier, with less velocity in general. In a paper by Knack & Keefer, they estimate that a 10-percentage-point increase in the share of people who say “most people can be trusted” is associated with about +0.8 percentage points of annual per-capita GDP growth. Mechanically, an extra 0.8pp of growth sustained for 20 years is roughly +17% higher GDP per capita; over 30 years, roughly +27%.

3. When Food, Commerce, and Retail Blur

Another thing I didn’t expect was how naturally food and commerce blend. You walk into an Italian restaurant and find shelves of Italian products for sale: olive oil, pasta, sauces. They dropped the boundary between eating and buying ingredients, and you find it in so many places for different cuisines.

This blur makes the business model more resilient. Revenue comes from multiple streams. Customers engage differently: browsing, tasting, buying. The space works harder.

4. Food is expensive but high quality, including vegan options

One detail surprised me: hotels themselves aren’t that expensive. A well-located three or four-star hotel often costs roughly the same as a comparable hotel in Casablanca.

But, the big difference is food. A mid-range restaurant runs between 40 to 60 euros per person. Supermarket prices are similarly high. But you can also feel that the quality of ingredients is significantly better.

I wandered randomly into Tibits at Lucerne train station. It’s a buffet where you pay CHF 4.50 per 100 grams. When I started choosing food, I asked if there was pork, and the server told me it’s a vegetarian restaurant. The food was so good that they don’t even need to market it as a vegetarian restaurant. I found out that 80% of their customers today aren’t even vegetarian. they come simply because the food is that good.

5. Tourism as a Coordinated System

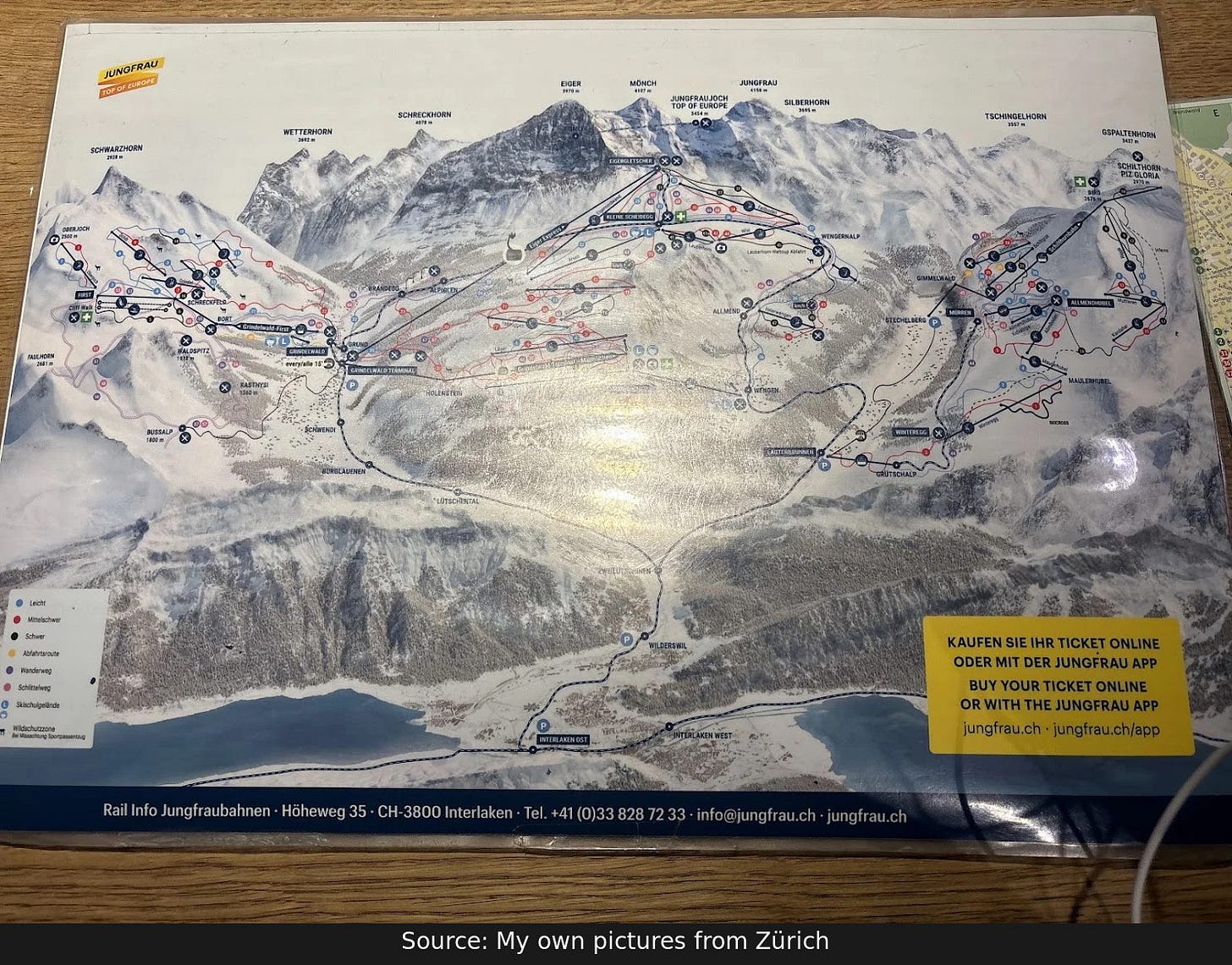

What struck me most in Switzerland wasn’t the mountains. It was the systems behind them. Even in small, remote villages, I found the same thing: structured maps, curated activities, clear signage. Hotels provide free public transport passes. Ski lockers let you store gear so you’re not hauling equipment daily. Live webcams show real-time conditions at 3,500 meters. So you can decide whether to commit your day before leaving the hotel.

The Jungfrau region is the clearest example. The Jungfraujoch, Europe’s highest railway station at 3,454 meters, isn’t impressive because of altitude alone. It’s impressive because everything around it connects: transport, accommodation, equipment rental, information systems. Each piece designed to reduce friction.

That trail map I picked up in a Swiss village wasn’t just a brochure. It was decades of coordinated investment, made visible. Switzerland figured out something important: tourism infrastructure isn’t about building attractions. It’s about building systems that make attractions accessible, enjoyable, and worth returning to. The goal isn’t to attract visitors once—it’s to make the experience so seamless they keep coming back.

6. Museums as Engaging Experiences, Not Storage Rooms

I visited more than six museums across the country, from the FIFA Museum, to the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Museum, the Patek Philippe Museum, the Jungfraujoch Ice Palace at the Summit of Europe, and CERN Science museum. Different topics, same execution quality. These are not museums frozen in 1990s logic: long walls of text and silent objects. The experience is properly designed: short explanations, strong storytelling, a constant mix of video, audio, physical artifacts, archives, and interactive elements to help the visitor understand.

Every museum has permanent exhibitions for depth and temporary exhibitions for renewal. A reason to return. At CERN, they have live science workshops every Saturday. I went there randomly and found a room with more than 300 people attending.

With the Swiss Travel Pass, all of these museums are free to enter. I didn’t even know that when I bought it. What a good surprise.

7. Design Culture You Can Feel in Everyday Apps

Train apps, luggage systems, booking flows, payment systems… the level of detail they get right is striking. You can tell these products were built by people who know what they’re doing. Edge cases are handled. Friction is anticipated. Nothing feels flashy, but nothing feels careless.

Swiss design has always prioritized clarity over decoration. In the 1960s, Swiss designers built a movement that became the default language of modern design: grids over decoration, typography over illustration, white space over density, neutrality over emotion. Design wasn’t meant to impress. It was meant to work.

When you compare the SBB app to other rail apps, the difference is clear. Every interaction is considered and well thought. All the hidden details, the evolution of features before you get to the train, once you are in after or once you leave. You don’t even notice the design because it never gets in your way.

8. Shared Prosperity and Value Distribution Through Franchises and Cooperatives

When traveling, I always research companies I see repeatedly on the street. What’s the story behind them? Why do they look like this?

It’s clear that Switzerland is not the country of fragmented small businesses. In retail at least, most stores belong to well-organized chains or cooperatives. Every store looks like part of a big system with a well-thought brand.

I found some good surprises in terms of business models. k kiosk is a chain of small retail kiosks. You find it everywhere: train stations, street corners, shopping centers. What’s interesting is how they scaled, not through direct employment, but through an agency partner model. Each kiosk is run by an independent operator who gets a commission from the store’s total revenue. Which makes incentives aligned 100% that no labor contract can replicate.

The two major grocery stores are Migros and Coop, and they are both cooperatives. Migros founder transformed the company into a cooperative. He gave his shares to his registered customer for free as he wanted to ensure the company would serve the public interest rather than profit.

There are parts of Switzerland economy where participation in value creation comes with participation in value capture. Franchises let small operators plug into large systems without being crushed by them. Cooperatives let consumers and workers keep value that would otherwise flow to distant shareholders.

9. Payment Without Friction

Six years ago, 70% of Swiss payments were cash. In 2025, it’s 24%. Several places I visited didn’t accept cash at all. The shift happened faster than anyone expected.

TWINT is the reason. QR codes everywhere: restaurants, parking meters, vending machines. What’s striking about TWINT is that it’s not a governmental initiative like UPI in India or PIX in Brazil. It’s a private consortium of 6 banks that became a national standard purely through adoption.

They fast-tracked adoption by making the app 100% free for end users and charging merchants 1.3%. When users pay, the bank checks the balance in real-time. The money is debited directly. There is no “top-up” required. There is no/limited informality in Swiss economy which is a critical factor.

A Pattern, Not a Coincidence

At some point, these observations stop being separate. Reliable systems and infrastructure, trust, self-service, great value distribution model, they reinforce each other. It’s a loop.

Switzerland is small, wealthy, and has had centuries of stability to compound these investments. Not every lesson transfers directly. But It’s about what happens when a society invests at the same time in its infrastructure, the systems and norms, and its people.

I can certainly second the observation about the SBB app. It is the best public transport app I have ever used, including CityMapper and Google maps. It is amazing.

Of course that is partly because of what you mentioned: that the whole timetable down to the local postal buses is coordinated.