The Lab, The Factory, and The Theatre

A framwork of how companies actually spend their time

Over the past 10 years, I’ve studied dozens of organizations. Either as a consultant, an operator, and through hundred of hiring conversations. Different sectors, countries, stages. The details varied, but the pattern didn’t. Recently, while interviewing a candidate from a large bank, I tried to explain how two companies could operate in fundamentally different modes. The conversation clarified something I’d been circling for years.

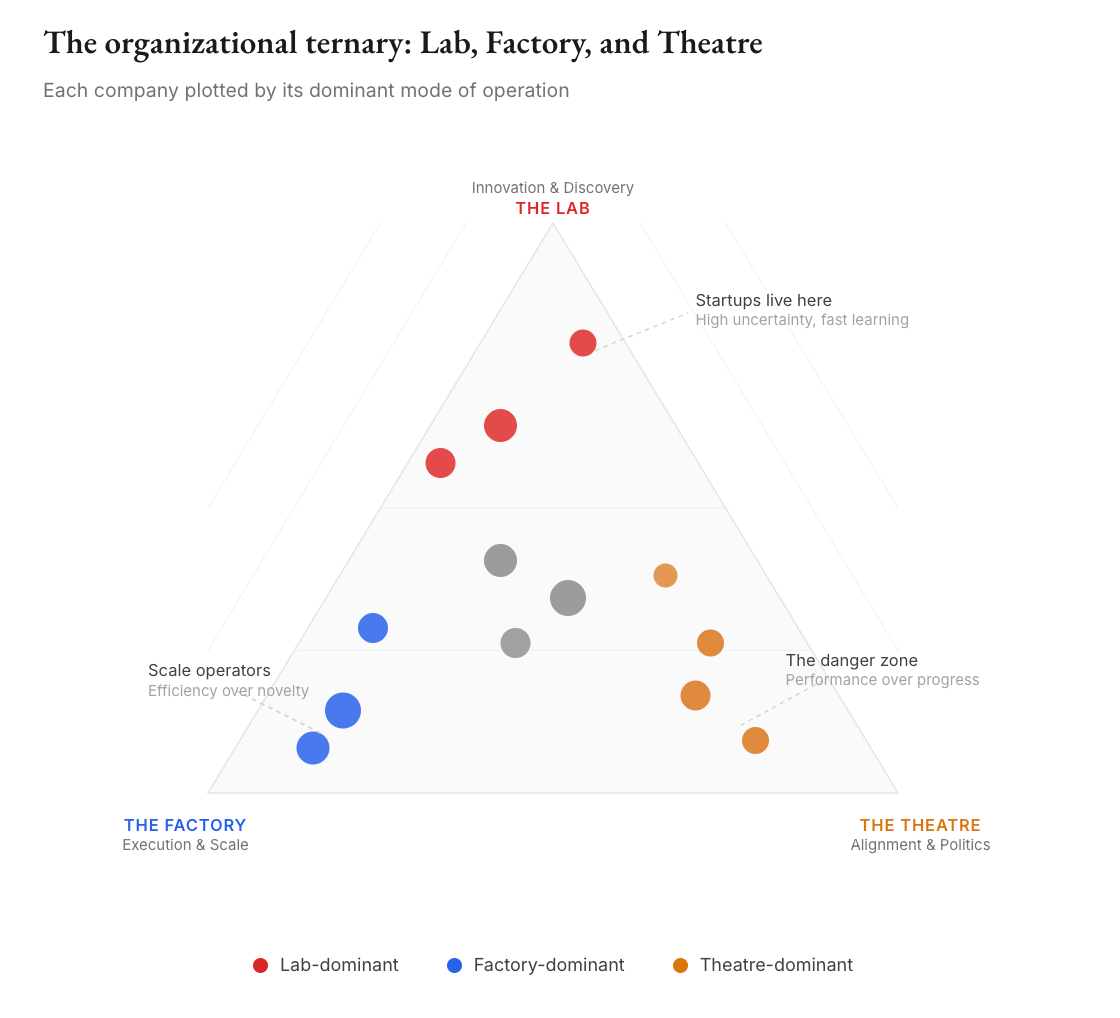

Every company operates through three modes, not departments or org chart boxes, but ways of spending time. I call them the Lab, the Factory, and the Theatre. Every company is a mix of all three. The question is never “which mode?” but “what ratio?” and whether that ratio fits your context.

The Lab

The Lab is where uncertainty lives. Companies build new things without knowing if they’ll work. New products & markets are invented & discovered. The Lab is inefficient by design. Its job is to learn, not produce.

Early-stage startups are mostly Lab. They can look foolish. They can waste effort in exchange for insight. When a startup loses its Lab too early, it doesn’t mature, it dies.

The Factory

The Factory is where value becomes real & things get made. Products, services & systems run. Reliability matters more than novelty. The Factory takes what the Lab discovered and makes it repeatable. It replaces improvisation with process, heroics with discipline. The Factory is about flow and leverage: turning one unit of effort into ten units of output.

As companies grow, the Factory takes over. Without it, success collapses under its own weight. The tragedy of many young companies isn’t that they fail to innovate, it’s that they never learn to operate. The Factory is often dismissed as boring. In reality, it’s where most economic value is created. A great Factory compounds quietly. Toyota’s production system or Costco’s supply chain aren’t glamorous. They’re generational wealth engines. It’s when Boring is Beautiful.

The Theatre

The Theatre is everything else. Meetings, workshops, off-sites, steering committees, culture sessions, status updates. It’s how organizations talk to themselves about work.

Theatre isn’t bad. In fact, it’s the glue that holds the Lab and Factory together. It helps people share context, reduce misunderstandings, and coordinate at scale. Good Theatre clarifies. It shortens feedback loops. It prevents people from pulling in opposite directions. A strong vision & culture is necessary to attract A+ talent. Bad Theatre does the opposite. It exists to signal importance, protect territory, avoid decisions, or simulate progress. Organizations rarely notice when they cross the line as from the inside, it still feels like work.

Context matters. A bank needs more Theatre than a startup, regulators demand it. A 500-person company needs more coordination than a 20-person one. Theatre isn’t the enemy; unnecessary Theatre is. The goal isn’t zero—it’s minimum viable Theatre for your size and sector.

How the balance shifts

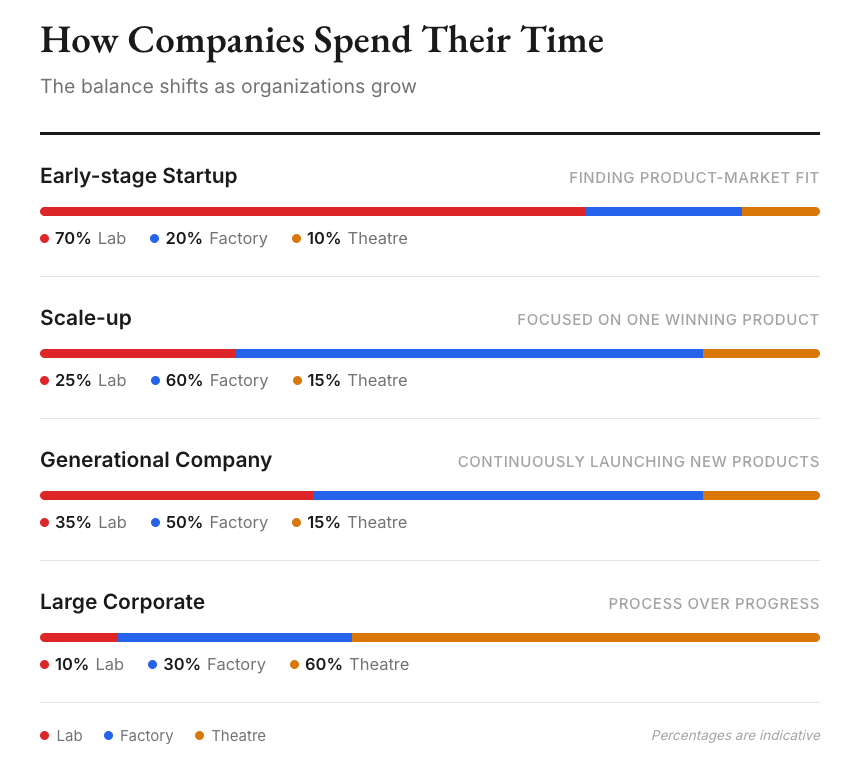

The proportion of Lab, Factory, and Theatre in every organization varies & changes over time.

A startup starts mainly as Lab. Just enough Factory to function, just enough Theatre to stay aligned & the team motivated. As it scales, the Factory takes over. When the business model stabilizes, 99% of companies shift into Theatre-heavy companies & less than 1%, generational companies where the the lab takes over again to launch new products & markets.

Those who shift into Theatre-heavy mode. They almost never recover (though there are exceptions). Once most energy goes into managing internal dynamics rather than creating or delivering value, decline becomes slow but inevitable. Companies instinctively try to fix it with more meetings about why production is failing, more alignment sessions, more steering committees.

However, exceptional companies manage to resist this gravity. Some, whether through founder intensity, operational obsession, or cultural discipline, operate at massive scale while keeping an unusually large Lab alive and an unusually small Theatre.

The balance between Lab, Factory, and Theatre is shaped more by leadership & less by the structure. Some leaders are natural builders who thrive in the Lab. Others are operators who bring order and scale. Still others specialize in the Theatre, skilled at navigating people, narratives, and power. A leader can be excellent in one phase and harmful in the next.

Why Theatre expands & how to reduce it

Theatre grows when three things are missing. The first is clear goals. When success is ambiguous, discussion replaces execution. The second is shared information. When knowledge is unevenly distributed, alignment turns into negotiation, and negotiation turns into politics. The third is aligned incentives between individual goals & company goals. When these three are absent, Theatre becomes the default mode of survival.

But there’s a deeper force at work. Theatre expands because it’s the path of least resistance for individual survival. The Lab requires tolerating failure and ambiguity. The Factory requires discipline and accountability to measurable output. Theatre requires neither. It rewards articulation over action, presence over production. When personal risk increases, people rationally migrate to where they can demonstrate value without being measured on outcomes.

Theatre weight can also be cut, but not without cost & needs a lot of courage. When Musk took over Twitter’s, he removed both Theatre and Factory alike. Systems broke. Advertisers fled. However, when this happens & done well, something interesting occurs. People naturally migrate back to where value is created. They spend more time in the Lab or the Factory, depending on what the company actually needs while Theatre stops being the center of gravity.

How to spot a Theatre-heavy company

For operators choosing where to work, Theatre-heavy companies reveal themselves early if you know what to look for. They rely heavily on consulting firms, not occasionally for sharp, well-scoped problems, but continuously, across functions & initiatives as if thinking and conviction had been outsourced. It signals an organization that no longer trusts its own judgment. They are also perpetually “in transformation,” doing workshops, and roadmaps, even though real transformation cannot be permanent.

They’re obsessed with forecasting. Plans are rewritten constantly, and business planning becomes a full-time job rather than a constraint around execution. The future is discussed in detail while the present moves slowly. These aren’t signs of ambition. They’re signs of stagnation, a warning that most of the energy will go into explaining & aligning the work rather than doing it.

Theatre-heavy companies also reveal themselves through how they communicate. Meetings proliferate without clear decisions, status updates that could be async, alignment sessions that align nothing, workshops that produce frameworks instead of work. The written equivalent is just as telling: emails that copy everyone, send “updates” with no actionable content, or exist solely to signal activity. In both forms, communication stops being a tool for coordination and becomes a currency for survival. When outcomes are unclear, visibility becomes the metric. In healthy organizations, meetings and emails move work forward. In Theatre-heavy ones, they become the work itself.

At the individual level, people starts explaining instead of creating. They abstract instead of deciding. They comment instead of owning outcomes. Teaching is only valuable when it transfers capability.

The same modes, at the human level

These modes also describe how individuals spend their time on a daily basis and change significantly through their career.

Lab: Learning something new, building a skill, experimenting with an approach you haven’t tried before.

Factory: Producing deliverables, executing on known processes, generating measurable output.

Theatre: Managing perceptions, attending alignment meetings, signaling activity.

Career arc:

Early career: Lab-heavy. Building skills, taking risks.

Mid-career: Factory-focused. Valued for execution and delivery.

Senior roles: Risk becoming Theatre-dominant through alignment and stakeholder management.

The best operators stay close to the Factory by making concrete decisions, staying accountable to metrics, using Theatre only to unblock and clarify.

Closing thought

Every company has a Lab, a Factory, and a Theatre. Most don’t fail because they lack talent, vision, or ambition. They fail because they slowly replace creation and execution with performance. The best companies aren’t the ones with no Theatre. They’re the ones that never forget what Theatre is for.

I ask myself a simple question every week: Where did my time go: learning, producing, or performing? I’ve learned that my job isn’t to eliminate Theatre. it’s to constantly pull gravity back toward the Lab and the Factory.

Very interesting approach !